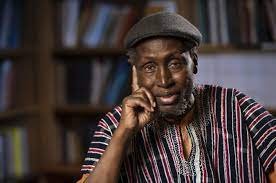

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Past and his Son’s Present Trauma

In a social media post that has become a topic of widespread discussion, Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ, son of one of Africa’s most revered literary giants, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, has made it public that his father beat up his mother on several occasions while he (Mũkoma) was growing up.

“Some of my earliest memories are me going to visit her at my grandmother’s, where she would seek refuge.” He wrote on the X platform.

As we try to understand Mũkoma’s actions, we need to ask questions about the nature of the existing family and community relationships in Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s family that might have pushed Mũkoma to vent his frustrations in the public domain. Is the global court of public opinion a veritable platform for nailing erring and unreachable family members? In the light of African traditional intra-family dispute settlement mechanisms, could it be inferred that Mũkoma’s choice of action portends a rising or even prevalent trait among young people, starved of deep-rooted extended family and community connections and culture?

From his recent social media posts, Mũkoma is hurting deeply at the unending remembrance of childhood memories of going to meet her beaten-up mother at her father’s house. As a grown man, he has a grievance. But this grievance is against a father who his mother once described in an interview as a very responsible father. She further described him as a man who loved and cared for his children. This characterisation of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o seems believable given that Mũkoma has yet to state a case of abandonment or irresponsibility on the part of his father. Mũkoma’s emotional wounds need healing. Yet, it appears that, like many young people today, he does not have access to traditional African community frameworks for intra-family dispute settlement. In the absence of such critical mechanisms and feeling a strong urge to unburden his soul, he goes to the general public, a place where his pains will surely be compounded.

The illusion of social media as community

“You all are my family!” How many times have we heard social media influencers address their followers with such language? But we know, and they know, that it is simply not true. The whole world cannot be your family. People who gravitate towards you because of your talent – which represents just one singular aspect of the complexity of a person’s being – simply do not qualify as family. Neither do they qualify as community, which is next to family in the natural social order of life.

But many city-raised young people today have little comprehension of this reality. Born to parents who are too busy making ends meet, they have been raised by nannies, daycare centres and schools. From childhood, they have been separated from deep and sustained connections with extended family, kindred and community, thus being estranged from the connections that would have instilled meaningful values and enriched them emotionally. Taught in the colonial language and made to consider culture and community as unimportant, these people have been raised to believe that happiness and success in life are mostly about networking and career. This narrow definition of life that is devoid of the central role of close family and community results in adults who grapple with life issues that they are not equipped to handle by themselves.

The complexity that has become Mũkoma’s reality after the revelation on social media became evident days after the tweet. Mũkoma released a follow-up tweet, stating that life has been really difficult as a lot of hate is being thrown his way for the revelation he made against his father. He had become a pariah to family and friends. But also, he was glad that some people were coming out to tell their own stories of family abuse. In a latest tweet, he said he understood why relatives and his father’s friends were upset with him but that it was surprising that his own close friends would not talk to him, as well.

Intra-family dispute settlement

In many African cultures, men are expected to grow up and ask questions of their parents. That is why parents are usually careful how they act, knowing that children will grow up to question them about certain aspects of their existence. No parent wants to lose a child’s respect in such deep and lasting ways as being unable to logically provide reasonable arguments to justify their decisions. However, such questioning is usually done within the security of the nuclear family. When the nuclear family fails to provide a conducive and impartial space for such, the case is taken by the grown children of the aggrieved party to the extended family where such discussions are held. If the extended family is not equipped to act as an independent arbiter, then a kindred or lineage meeting is called. The case gradually grows to the village level.

Community restoration and healing

There are major differences between the community-led conflict resolution that many African communities engage in when settling family disputes and public spaces such as Twitter. First, the emphasis, as it seems on social media, is naming, shaming, blaming and banishment, which is very much a Western approach to addressing conflict. On the other hand, the community-led conflict resolution approach of many African communities is to find reasons for such unbecoming behaviour, rehabilitate and reintegrate the offender, and prevent repeat offences.

What happens in such community led engagements (with involved family members) is that elders on both sides – the husband and wife’s families, in this instance – who are armed with institutional memory are able to have conversations and try to arrive at the root cause of the misbehaviour. In the case of domestic violence, for instance, elders and arbiters will explore the crime – the person or persons involved in the crime, the accuser and the accused – as well as its remote and immediate causes.

In trying to get to the root of the vice, the arbiters might ask the question: Why was a younger Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o a wife beater? Perhaps Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o grew up seeing his own father beat up his mother. Perhaps he also observed his uncles on his father’s side beat up their own wives, a vice that runs in the family. Could the reasons for his misbehaviour towards his wife be generational? Ngugi’s plea for mitigating circumstances might invoke his youth and fame as having led to his lack of judgement. As an older man now, he may explain the situation and context to his children and extended family, in-laws and kindred. He may state that he is a changed man, a beneficiary of wisdom that comes with old age.

Hopefully, there might be a lot of positive testimonies coming from family members about the person he is at this time. That way, Ngugi’s children may be in a better position to forgive and heal from the trauma of watching their mother beaten up and disregarded.

Most likely, a remorseful Ngugi would ask for forgiveness from his own children, his in-laws, and every other person who was offended by his actions. If this happened, the children would come out with a sense of understanding of human frailty because no one is infallible. Further, we can also learn from the experience that we must be careful in the way we live, as one mistake could cost us precious relationships.

The whole idea is to humanize Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, if he is truly remorseful, and to bring deep and lasting healing to Mũkoma, his siblings and his late mother’s family. In doing this, Ngugi can play the role of a grandfather in the life of Mũkoma’s children. Remember that that is the whole idea. There are grandchildren coming into the family who need to know the unconditional love of a grandfather. These children need the knowledge that Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o carries and the image he embodies. They need the best of him. The community-based conflict resolution will ensure this kind of continuation.

This is not to say that in all cases, family and community can successfully mediate and bring closure to cases of human rights abuse within families. There are instances where erring family members are stubborn, adamant, and unremorseful. In that case, as we see in Things Fall Apart, where Okonkwo went on to murder Ikemefuna against the advice of his kinsmen, ruin usually follows such men. Usually, such men are people who are inherently dysfunctional, who are beyond remedy, and whose continued integration into society would cause more harm than good. In strong community-oriented cultures, as found in many traditional African societies, such people are few and far between.

Social media retribution

Unfortunately, with the social media mob justice kind of action, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is named and shamed. His entire life and personality are reduced to a wife-beater. Reducing people to their mistakes and errors is one of the hallmarks of Western culture – the cancel culture. Ngugi is declared persona non-grata and cut off from his grandchildren. The entirety of his being, the better side of him and all the knowledge he carries, which he could have bequeathed to his grandchildren and to generations after him, are sullied. Rather than children who grow up to be whole, proud of their lineage and in touch with the frailty of human errors, another generation will grow up who Google up their grandfather and partake in the shame that has been slammed on them as the grandchildren of a wife-beater.

Now, what is the way forward for the wa Thiong’o family? It is hard to say since Twitter allows for so few words to determine the real situation of things. No one knows if Mũkoma has previously talked to his father, and his father refused to acknowledge his mistakes. No one knows if Mũkoma has any connections with his father’s extended family or his mother’s extended family.

In the absence of all that information, it becomes hard to speak further. What is clear is that the publicity surrounding Mũkoma’s revelation has considerably weakened the wa Thiong’o dynasty for generations. As the Gikuyu proverb says, Andu matari ndundu mahuragwo na njuguma imwe, which loosely means that the absence of union spells weakness.